'45 is alive and well

The world was made in 1945.

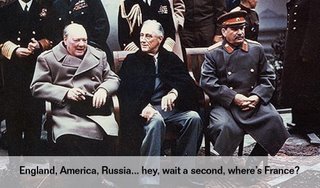

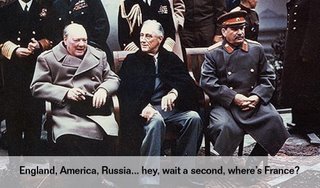

Not really. But the current order still reflects the mid- to late forties, when World War II ended and world was introduced to nuclear weapons, the United Nations, and the United States as the dominant global player. Even today, the UN Security Council (which is the closest thing to the authority of law and order in the world) is chaired by the five victors of WWII: America, Russia, Britain, China and France.

Not really. But the current order still reflects the mid- to late forties, when World War II ended and world was introduced to nuclear weapons, the United Nations, and the United States as the dominant global player. Even today, the UN Security Council (which is the closest thing to the authority of law and order in the world) is chaired by the five victors of WWII: America, Russia, Britain, China and France.

But like a middle-aged man who never grew past his days as a star high school quarterback, the current world order reflects a simpler, black-and-white era that has not adapted well to the modern day. As such, it’s always interesting to observe international political philosophers justify their positions by drawing comparisons to the Second World War and the events that immediately followed.

Neoconservatives (or Neocons, to their friends) constantly cite WWII as evidence that overgenerous diplomacy doesn’t work, that an appropriate display of muscle can keep evil at bay, and that an ounce of pre-emption is worth a pound of retaliation.

To Neocons, 1930-1945 presented a two-part saga. The first chapter tells of an appeasing Chamberlain and France that allowed Hitler to rearm, even sacrificing allied nations (Czechoslovakia, Austria) to avoid confrontation—only to come to the aid of Poland and the rest of Europe years too late. Episode Two puts the spotlight on a strong and unwavering Churchill, long ignored by peaceniks who refused to foresee the rise of Hitler, rolling up his sleeves and saving western civilization with blood, sweat, tears and Roosevelt.

Today, Neocons always want to see bold, cold leaders willing and able to do some dirty work for the greater good—and they’ll be the first to compare any international threat to Hitler, the very symbol of evil raised by appeasement. Essentially, Neocons await a Messiah in the form of a Churchillian leader, which is why I dub the school of Neoconservatism “The Church of Churchill.”

Institutionalists see the development, empowerment and legitimization of international organizations (e.g. the United Nations, World Bank, International Criminal Court) as the solution to the absence of international law and order.

Most Institutionalists (particularly those in Europe) view the carnage of WWII as evidence that war is a horror which should be, at worst, a last resort, and at best taken off the table entirely. They cite the generous Marshall Plan as proof that providing aid and promoting peaceful behavior is the sure way to defuse violent attitudes. Despite their worship of the Marshall Plan, Institutionalists seem to ignore that it was only made possible after Germany had surrendered as a result of total military defeat and destruction.

As for the United Nations, Institutionalists see a strong and impartial authority of acting as judge, jury and executioner as necessary—regardless of the fact that the UN is not particularly strong (we’re in Baghdad, aren’t we?) or impartial, and therefore not much of an authority.

Isolationists believe that each country (particularly the US) should do its best to avoid international meddling, and would benefit most by focusing on economic issues and its own social and technological advancement.

With the approach that little good can come from political entanglements, Isolationists point to the fact that both World Wars were the result of the Franz Ferdinand assassination in the Balkans. Wars have existed since the beginning of mankind, but the World Wars (generally accepted as humanity’s worst events) are the direct result of sending your own boys to fight someone else’s battle. Tens of millions dead, the destruction of countless cities, nations and even empires, and the reversal of economic advancement—these are the casualties of getting too involved overseas.

Even today, Isolationists believe any US political or military involvement abroad does more damage than good, and suggest that the billions of dollars spent each year on defense could vastly improve our social services while propelling our economy well past the reach of others.

International Realists cite that in the end, the world is not a struggle of good versus evil, but rather an arena of strong and weak nations that may combine or oppose one another for their own ends.

The Realist suggests that WWII ended when the most powerful combination of nations won thanks to superior firepower, better coordination and geographic advantage. Democracy had nothing to do with it—after all, the defeat of Hitler was mostly thanks to the strength of Soviet Russia—and we would be keen to arrange our alliances today based on mutual interests rather than political ideology. In this regard, it doesn’t matter if our allies are democracies or dictators, as long as they make us stronger and help us work towards our goals.

A pure Realist may see 9/11 as our own Pearl Harbor: the jolt that woke a sleeping giant and, for better or for worse, led to grander events.

World War II, its causes and its aftermath may be the most heavily measured and analyzed case study in history. As a result, nearly any international political philosopher can prove their own point—and disprove the position of their opponents—by selectively citing any set of stimuli and results that best represents their view.

In the end, we must acknowledge that the world has changed since 1945 (even if the UN Security Council has not), and we should stop overusing WWII analogies. Unless, of course, you want to know who the next Hitler will be.

Not really. But the current order still reflects the mid- to late forties, when World War II ended and world was introduced to nuclear weapons, the United Nations, and the United States as the dominant global player. Even today, the UN Security Council (which is the closest thing to the authority of law and order in the world) is chaired by the five victors of WWII: America, Russia, Britain, China and France.

Not really. But the current order still reflects the mid- to late forties, when World War II ended and world was introduced to nuclear weapons, the United Nations, and the United States as the dominant global player. Even today, the UN Security Council (which is the closest thing to the authority of law and order in the world) is chaired by the five victors of WWII: America, Russia, Britain, China and France. But like a middle-aged man who never grew past his days as a star high school quarterback, the current world order reflects a simpler, black-and-white era that has not adapted well to the modern day. As such, it’s always interesting to observe international political philosophers justify their positions by drawing comparisons to the Second World War and the events that immediately followed.

Neoconservatives (or Neocons, to their friends) constantly cite WWII as evidence that overgenerous diplomacy doesn’t work, that an appropriate display of muscle can keep evil at bay, and that an ounce of pre-emption is worth a pound of retaliation.

To Neocons, 1930-1945 presented a two-part saga. The first chapter tells of an appeasing Chamberlain and France that allowed Hitler to rearm, even sacrificing allied nations (Czechoslovakia, Austria) to avoid confrontation—only to come to the aid of Poland and the rest of Europe years too late. Episode Two puts the spotlight on a strong and unwavering Churchill, long ignored by peaceniks who refused to foresee the rise of Hitler, rolling up his sleeves and saving western civilization with blood, sweat, tears and Roosevelt.

Today, Neocons always want to see bold, cold leaders willing and able to do some dirty work for the greater good—and they’ll be the first to compare any international threat to Hitler, the very symbol of evil raised by appeasement. Essentially, Neocons await a Messiah in the form of a Churchillian leader, which is why I dub the school of Neoconservatism “The Church of Churchill.”

Institutionalists see the development, empowerment and legitimization of international organizations (e.g. the United Nations, World Bank, International Criminal Court) as the solution to the absence of international law and order.

Most Institutionalists (particularly those in Europe) view the carnage of WWII as evidence that war is a horror which should be, at worst, a last resort, and at best taken off the table entirely. They cite the generous Marshall Plan as proof that providing aid and promoting peaceful behavior is the sure way to defuse violent attitudes. Despite their worship of the Marshall Plan, Institutionalists seem to ignore that it was only made possible after Germany had surrendered as a result of total military defeat and destruction.

As for the United Nations, Institutionalists see a strong and impartial authority of acting as judge, jury and executioner as necessary—regardless of the fact that the UN is not particularly strong (we’re in Baghdad, aren’t we?) or impartial, and therefore not much of an authority.

Isolationists believe that each country (particularly the US) should do its best to avoid international meddling, and would benefit most by focusing on economic issues and its own social and technological advancement.

With the approach that little good can come from political entanglements, Isolationists point to the fact that both World Wars were the result of the Franz Ferdinand assassination in the Balkans. Wars have existed since the beginning of mankind, but the World Wars (generally accepted as humanity’s worst events) are the direct result of sending your own boys to fight someone else’s battle. Tens of millions dead, the destruction of countless cities, nations and even empires, and the reversal of economic advancement—these are the casualties of getting too involved overseas.

Even today, Isolationists believe any US political or military involvement abroad does more damage than good, and suggest that the billions of dollars spent each year on defense could vastly improve our social services while propelling our economy well past the reach of others.

International Realists cite that in the end, the world is not a struggle of good versus evil, but rather an arena of strong and weak nations that may combine or oppose one another for their own ends.

The Realist suggests that WWII ended when the most powerful combination of nations won thanks to superior firepower, better coordination and geographic advantage. Democracy had nothing to do with it—after all, the defeat of Hitler was mostly thanks to the strength of Soviet Russia—and we would be keen to arrange our alliances today based on mutual interests rather than political ideology. In this regard, it doesn’t matter if our allies are democracies or dictators, as long as they make us stronger and help us work towards our goals.

A pure Realist may see 9/11 as our own Pearl Harbor: the jolt that woke a sleeping giant and, for better or for worse, led to grander events.

World War II, its causes and its aftermath may be the most heavily measured and analyzed case study in history. As a result, nearly any international political philosopher can prove their own point—and disprove the position of their opponents—by selectively citing any set of stimuli and results that best represents their view.

In the end, we must acknowledge that the world has changed since 1945 (even if the UN Security Council has not), and we should stop overusing WWII analogies. Unless, of course, you want to know who the next Hitler will be.

Yes, a pretty comprehensive classification of the existing approaches. Though, I would slightly change the conclusion. We shouldn't overuse WWII analogies, but not because the world changed since then but because these are not the only analogies in existance. The world always changes, of course, but this doesn't mean that all prior events become irrelevant, just that not all of them remain relevant. So, what's needed is to identify the invariants, those things that keep reappearing under various guises, while rightly rejecting those things which are accidental to specific time and place, highly unlikely to be repeated. And, in order distinguis the invariants from the accidentals, one should have more (preferably, way more) examples than one.

So here is the problem with WWII. Since it looms so large, it often blinds us to the fact that there were other highly consequential wars in history. WWI, of course, but one may consider the US Civil War, the Napoleonic wars, the 30 years war, the 7th century Muslim conquests, even back to the Punic wars and the Peleponesian war. All these are case studies and they all have some lessons to teach. And, of course, some stuff which is no longer relevant, as well.